As a standard part of the UX process, designers create information architecture when building products. Defining every avenue and path that users can take through an app or website, information architecture is much more than just a sitemap to show what page leads where.

Similar to building architects using a blueprint to construct every part of a house, from physical structures to more complex inner workings like electrical and plumbing, information architecture describes the hierarchy, navigation, features, and interactions of a website or application. And just as blueprints are the most valuable document for an architect to use in the construction of a building, information architecture can be the most powerful tool in a designer’s arsenal.

However, developing one isn’t as simple as putting a list of features together and mapping out how they work—let’s investigate the process.

What Is Information Architecture, and Why Is It Important?

Information architecture (IA) is, like a blueprint, a visual representation of the product’s infrastructure, features, and hierarchy. The level of detail is up to the designer, so IA may also include navigation, application functions and behaviors, content, and flows. There is no set limit to the size or shape of IA; nevertheless, it should encompass the generalized structure of the product so anyone (theoretically) should be able to read it and understand how the product works.

We’ll use the blueprint reference often because the purpose of both documents is nearly identical. Just like a blueprint, IA provides designers (as well as product development and engineering teams) a bird’s-eye view of the entire product. Having a single document that delivers a simple and understandable representation of how the application or website works is vital for developing new features, updating existing ones, and for seeing what is possible considering the existing product.

With IA available, it becomes significantly easier to make key decisions for new features and implementations, to understand timelines for product changes, and to follow user behavior through multiple processes.

Let’s dive into a basic video to see how an IA is built.

How to Design Information Architecture

As part of the UX process, IA design follows very similar patterns to flowcharting: Add shapes and connect them with lines in an organized fashion to a single document. The challenge when building IA is in understanding how your app or website actually works from the user’s perspective, and how to organize that information into a readable, legible format.

There are two major requirements for actually constructing IA: organizing it through a visual hierarchy (that is, a hierarchy of features, functions, and behavior) and creating a legend for displaying different types of features, interactions, and flows. With a standard flowchart, the shapes follow specific requirements (rectangles are processes, diamonds are decision points, etc.); however, following that nomenclature isn’t a requirement.

In other words, the most important factors to building your IA are where individual components of the architecture are placed (hierarchically), and how they’re labeled and displayed.

Understanding and Showing Visual Hierarchy

The most challenging aspect of creating a new information architecture is almost always in constructing it hierarchically. It’s a common misconception that IA must be built “from the top down.” That’s almost always more difficult to do unless it’s an existing product, such as in the video above.

When building IA from scratch, unless your website or application is following a standard format, drawing out anything after the top level is very difficult. It’s like asking a mechanic to build a car from the top down instead of in parts. Each piece has to be constructed in advance with its own research, time for design, and development. The same is true with IA.

Displaying visual hierarchy is a valuable asset to IA, not only because it provides better context for the reader, but also generalizes key regions of the product. If your app’s most significant feature is ordering a ride (a la Uber or Lyft) which can be done from the homepage, then that page will have the most touchpoints and the most value to the product. The same will be true for the visual hierarchy.

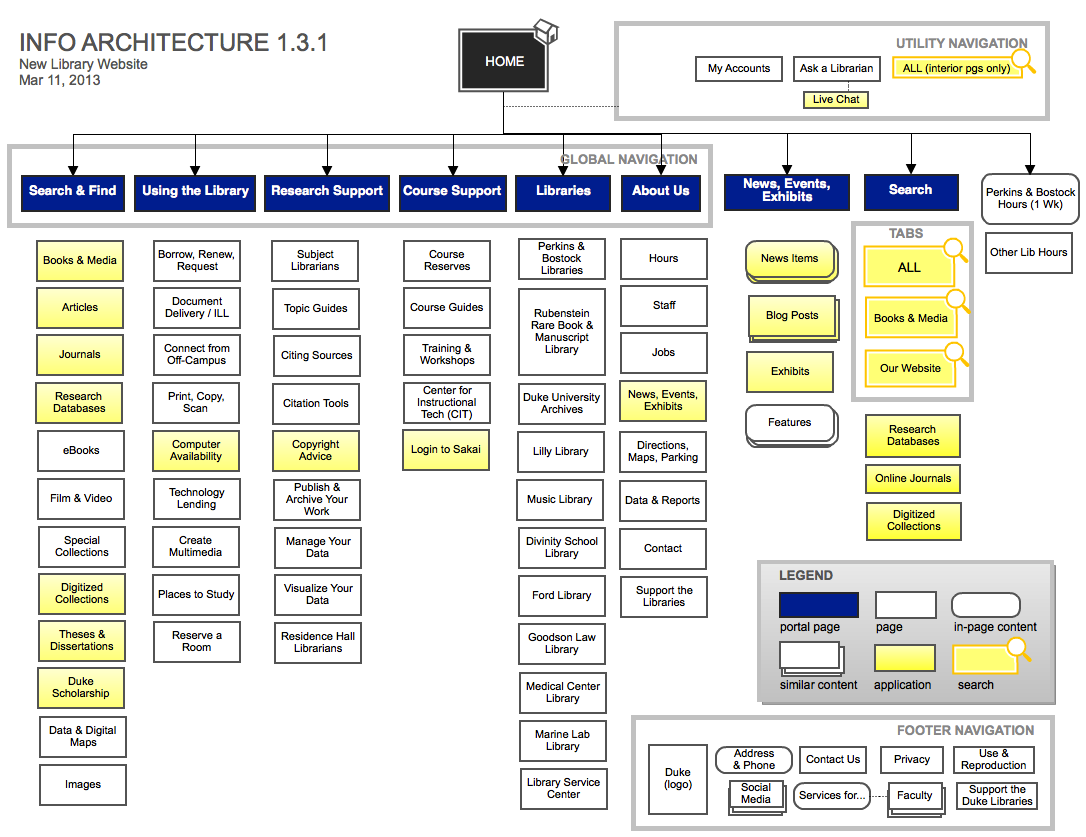

Sitemaps come in handy for understanding hierarchy since they organize pages numerically (such as 1.0 Home, 2.0 Payment, 2.1 Add Pay Method, etc.). Or consider the example in the image below for Duke University’s library website, where the top navigation isn’t only at the top but also highlighted to be visible across the entire application.

Hierarchy of Shapes, Colors, and Other Visual Elements

Aside from hierarchy, the architecture above does another thing well: It displays every engagement point uniquely as needed through a simple legend and a few key phrases. The legend denotes page and content type, and it signifies variations between colors of shapes. This is important because, though Duke’s site appears fairly simple, the IA only goes three levels deep. Each yellow rectangle denotes an application, so the processes within each of those boxes aren’t included in this document!

Even without those parts available, the structure is such that we can understand how to navigate the website through the IA alone. That stops when we reach an application within the website—it doesn’t have to.

The IA below is for a game. Using four shapes, no color, and smartly-placed text snippets, every major interaction is understandable without prototypes, and more importantly, it can be understood by anyone working on it.

This model isn’t perfect, but it organizes app hierarchy clearly and delineates what the user either sees or does at any given point.

The Best Information Architecture Tools

There are plenty of software applications that allow for building an IA, but few are simple and quick enough to make the experience enjoyable. Or at the very least, easy to manage.

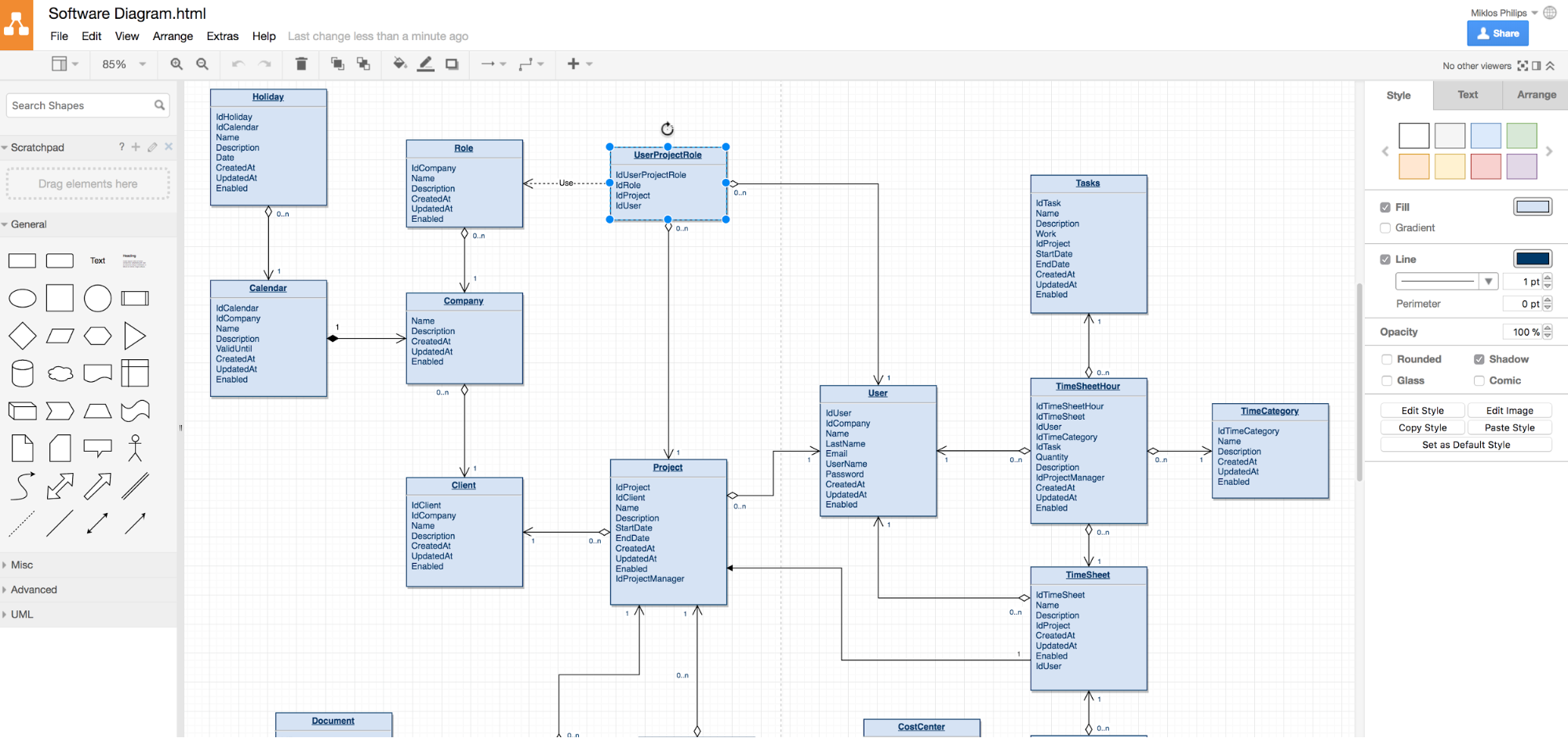

Draw.io, used in the video above, is completely free for personal and professional use and automatically plugs into Google Drive. It also has integrations with Confluence and JIRA, which are paid. Draw.io is excellent for flowcharting, creating user flows and information architecture, and with Drive functionality, multiple people can work on the same document and see changes live. There’s also a free offline version.

Lucidchart is another great tool that provides a slightly better experience than Draw.io and has additional benefits like pre-built templates, many more integrations, a mobile app (rated at 2.5 stars on the App Store), and support for enterprise.

Omnigraffle and Visio are long-time industry mainstays and work excellently for building and maintaining an IA design, though Visio is online only (the older offline version is Windows-only) whereas Omnigraffle is Mac-only and requires separate purchases for the MacOS and iOS versions. OmniGraffle has one benefit over the major competitors in that it provides JavaScript and AppleScript automation, which for most designers may be unnecessary, but typically, full-time information architects appreciate it.

All of the tools listed above are made for speed and ease of use, specifically around flowcharting, which follows nearly identical principles to information architecture. Other applications like Balsamiq, MindMeister, MindManager, or XMind all offer similar-style behavior but are built for other major purposes, such as prototyping or mind mapping.

Information Architecture Best Practices

While there are few defined rules for what constitutes information architecture, when going through the process, consider the following:

Don’t Focus on Hierarchy, Focus on Structure

Hierarchy is adjustable. The homepage will always be the homepage, but where it leads, how users get to those places, and everything in between and beyond is determined later.

All Processes Should Be Logical

Even though the IA in the UX process is for user interactions, every step of the way has to make sense. Registration screens shouldn’t lead to settings, a camera function shouldn’t jump to a map view…the list goes on.

Remember the UX Process

A common mistake is to just make IA, without resources, research, or other assets or work. That’s like telling an author to write a book without an outline, or a programmer to code an app without prototypes.

You Are the Cartographer

Cartographers take everything about a map into consideration, from mountain ranges to state borders. Just like map makers, designers determine what goes into the IA design. Individual pages, specific user behaviors, context for decision points… and so on.

Ultimately, the cartographer decides what goes on the map based on user needs. The same is true for designers, so construct the IA for the end user, namely the product development and design teams.

Information Architecture Is Ever-Changing and Evolving

To drill the point home once more, all IAs are built for change. Products evolve, designs change, users adapt, and the cycle continues, over and over. Don’t take it too seriously and know that there will always be room for improvement. Don’t aim for perfection; build a simple, adaptable IA.

My Information Architecture Is Done… Now What?

It’s a common conception that any design work is never truly done, and that’s certainly the case with information architecture. They grow and shrink and change as our products do. Unlike a blueprint for a building, IA will always evolve based on anything from user needs to new features or a product overhaul. Much of the structure may stay the same and provide consistency between versions so users don’t get confused.

And that’s a good thing. Knowing that IA is a fluid document—one that likely changes weekly, and sometimes even daily—is a powerful way to maintain the overall structure of your app or website without ever touching the code or creating new prototypes. The better the entire product development team knows the IA, the faster everyone will know what is and isn’t possible, and how serious any supposed “easy work” really is.

Which brings us to the real beauty of information architecture: There is no predefined starting point. While the traditional UX design process dictates that the IA is built after completing enough user flows; armed with plenty of user and competitive research, it can also be the first thing done… or the last. The prototyping process often brings up information on how certain behaviors or actions should occur that would be hard to imagine from a logical or unimaginative IA.

As an ever-evolving practice, IA design is an art as much as a skill, which is partly why large corporations have information architect positions. These designers are the gatekeepers of massive systems, and with their understanding of product growth over time, they help drive product, design, and engineering teams to make the right decisions over the span of years. That scale of organization isn’t for all designers, but every designercan build a simple, understandable information architecture.