The work of a UX designer happens in many different environments—from lean startups and Agile environments where teams work with little documentation, to consulting engagements for third-parties, or large enterprises and government entities with strict documentation requirements. Regardless of the nature of the engagement or environment (and the one thing that ties it all together), is a need for UX professionals to effectively communicate their design ideas, research findings and the context of projects to a range of audiences.

During the UX design process designers will produce a wide variety of “artifacts” and project deliverables as part of their UX design methodology. These may take many forms: deliverables help UX designers communicate with various stakeholders and teams, document work, and provide artifacts for meetings and ideation sessions. They also help create the “single source of truth” — guides and specifications for implementation and reference.

Here are the 10 UX deliverables a UX designer typically produces during an engagement. (This list is by no means comprehensive and may potentially be longer depending on the nature of the engagement.)

1. Business Goals and Technical Specifications

This is a fundamental step. For a UX professional it all starts with an understanding of the product vision, i.e. the reason for the product’s existence from a business perspective. Written in simple terms, the statement should include the problem being addressed, the proposed solution, and a general description of the target market. It should also describe the delivery platforms and touch lightly upon the technical means by which the product will be delivered.

It need not be longer than one page, but should describe the core of the What, Why and How. Here is an example: “The Fantastic App Co. has identified a gap in gift-giving applications on mobile platforms for the Millennial market (iOS and Android). A large number of Millennials have trouble remembering special dates, identifying the best gift, then finding and buying those gifts. Our solution is designed to alleviate that stress. Employing anticipatory design and the latest AI technologies the App delivers a useful and almost magical user experience.”

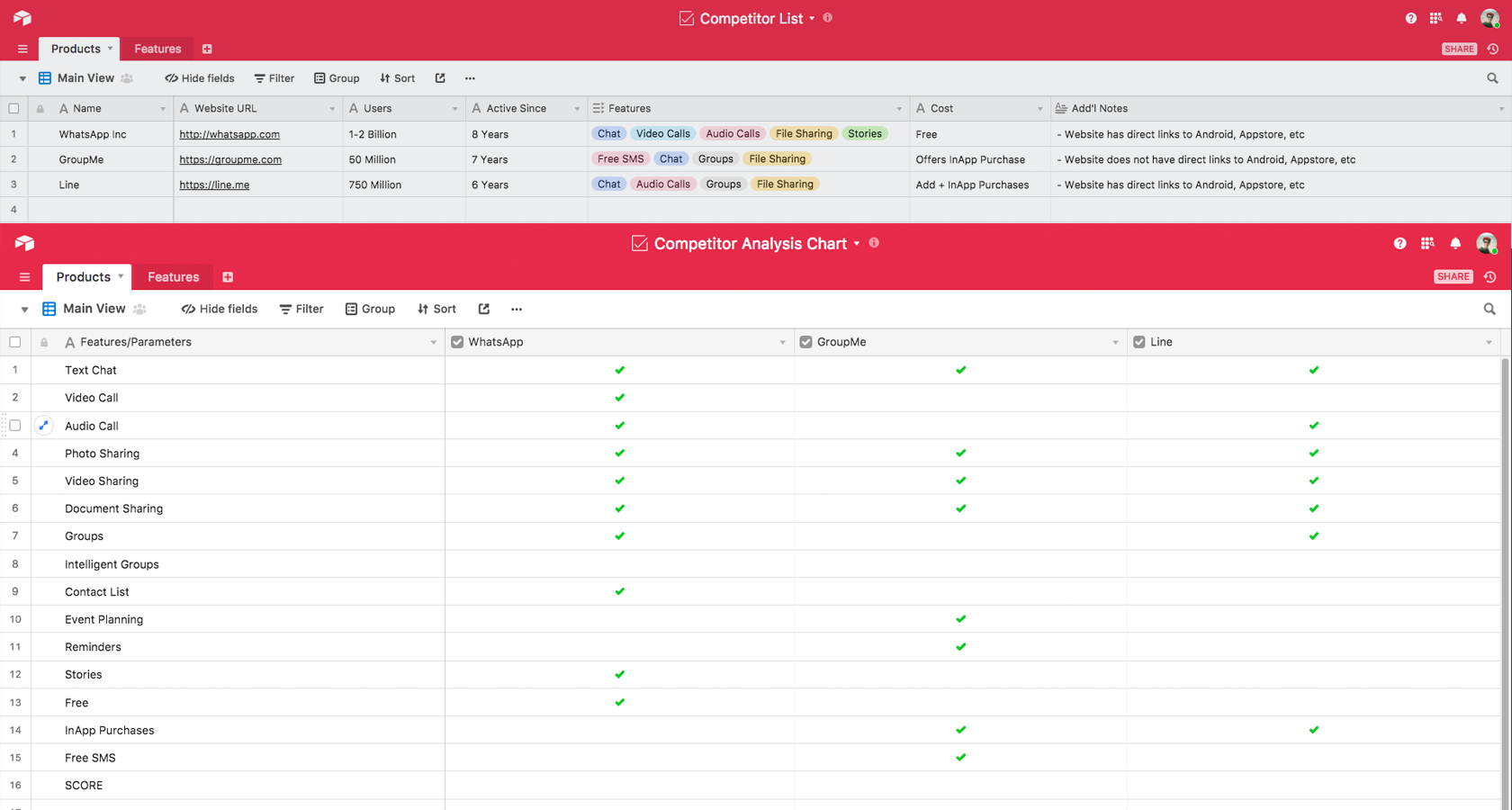

2. Competitive Analysis Report

For anyone starting to design a new product, it’s vital to make sure it’s a good market fit. Crucially, as part of a UX strategy the product must also have a compelling competitive advantage and a UX that is superior to others in the marketplace.

Competitive analysis means: “Identifying your competitors and evaluating their strategies to determine their strengths and weaknesses relative to those of your own product or service.”

One of a UX designer’s initial tasks is to research what products or services the target customers are currently using to solve the problem. Is there an equivalent product or service out there? Is there an alternative solution people are using that’s good enough but not perfect? A Band-Aid—a vitamin but not a painkiller? How can better UX make a difference?

A component of user experience research, a competitive analysis report identifies the top five competitors and examines what it is they are doing right, as well as what they’re doing wrong. This step will help set a design direction where clear goals are defined and the elements to be focused on spelled out.

A Competitor List and Competitor Analysis Chart (by Chandan Mishra)

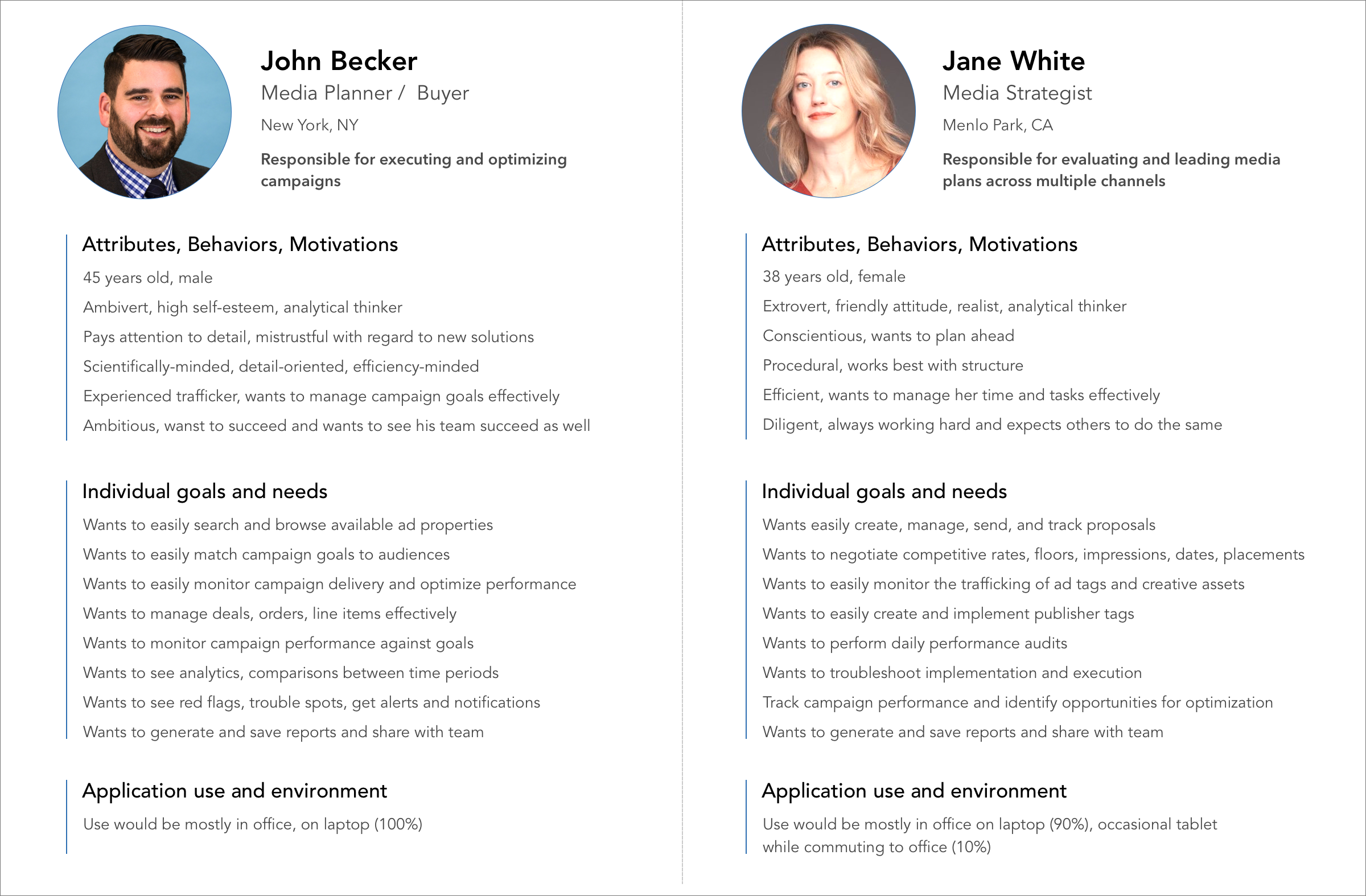

3. Personas and UX Research Reports

UX designers need to make sure stakeholders understand the needs of the product’s customers. Creating personas to encapsulate and communicate user behavior patterns and conducting user research are tried-and-true ways to do it. Personas are representative of a product’s typical users—by incorporating their goals, needs and interests, they help the team working on the project develop empathy towards the user.

User research is also an integral component in the UX design process. It involves a range of techniques used to extract behavioral patterns, add context and give insight into the design process. There are many types of user research tools and techniques available—it’s all about choosing the right “lens” for the right situation.

Before embarking on user research, it’s important to take the time to develop a research plan. This is a document that will help communicate research aims and methods as well as get buy-in from stakeholders. It is also a great tool that can be used to help keep everyone on track during the research project.

At the conclusion of the user research phase a report translating the research findings into actionable items is generated. The UX team is then set to design the product around those items.

Personas (by Miklos Philips)

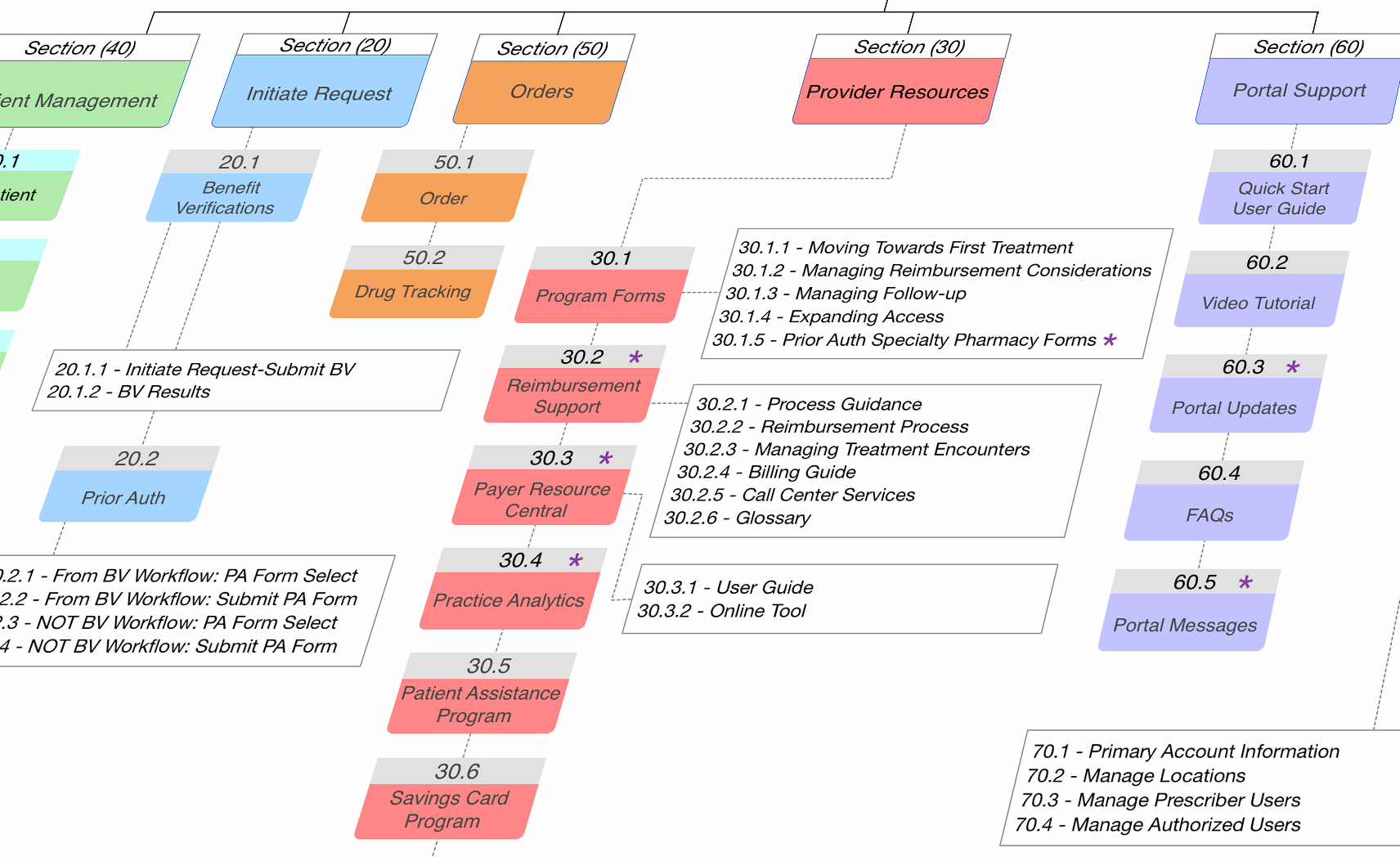

4. Sitemap and Information Architecture

A sitemap is a visually organized model of all the components and information contained in a digital product. It represents the organization of an App or site’s content. Along with wireframes, they are one of the most fundamental of UX deliverables and rarely skipped in a UX design process.

Sitemaps help lay out the information architecture—the art and science of organizing and labeling a product’s components—to support navigation, findability and usability; they also help you define the taxonomy and user interface.

Sitemaps are handy references to have as a resource and adjust as the product evolves based on iterative prototyping and user testing. During the design workflow, a numbering system is often employed to keep everyone on the same page when discussing the product’s content.

A sitemap, representing information architecture

5. Experience Maps, User Journeys and User Flows

An experience map is a visual representation that illustrates a user’s flow within a product or service—their goals, needs, time spent, thoughts, feelings, reactions, anxieties, expectations—i.e. the overall experience throughout their interaction with a product. It’s typically laid out on a linear timeline showing touchpoints between the user and the product.

User journeys and user flows are more about a series of steps a user takes, and demonstrate the way users currently interact—or could potentially interact with a product. They demonstrate behavior, functionality and the key tasks a user might perform. By examining and understanding the “flow” of various tasks a user might undertake, you can start to think about what sort of content and functionalities to include in the user interface, and what kind of UI the user will need to accomplish them.

Much of UX is about solving problems for users. When crafting a user journey, the designer needs to understand the persona, the user’s goals, motivations, current pain points and the main tasks they want to achieve.

What’s the difference between a user journey and user flow? Think of a user flow as the user working on one task or goal via your product or service, e.g. booking a car on Lyft; a user journey illustrates the bigger picture. A user journey expands beyond tasks, and looks at how a particular customer interaction fits into a larger context.

An experience map is crafted as part of a UX design process (by Miklos Philips)

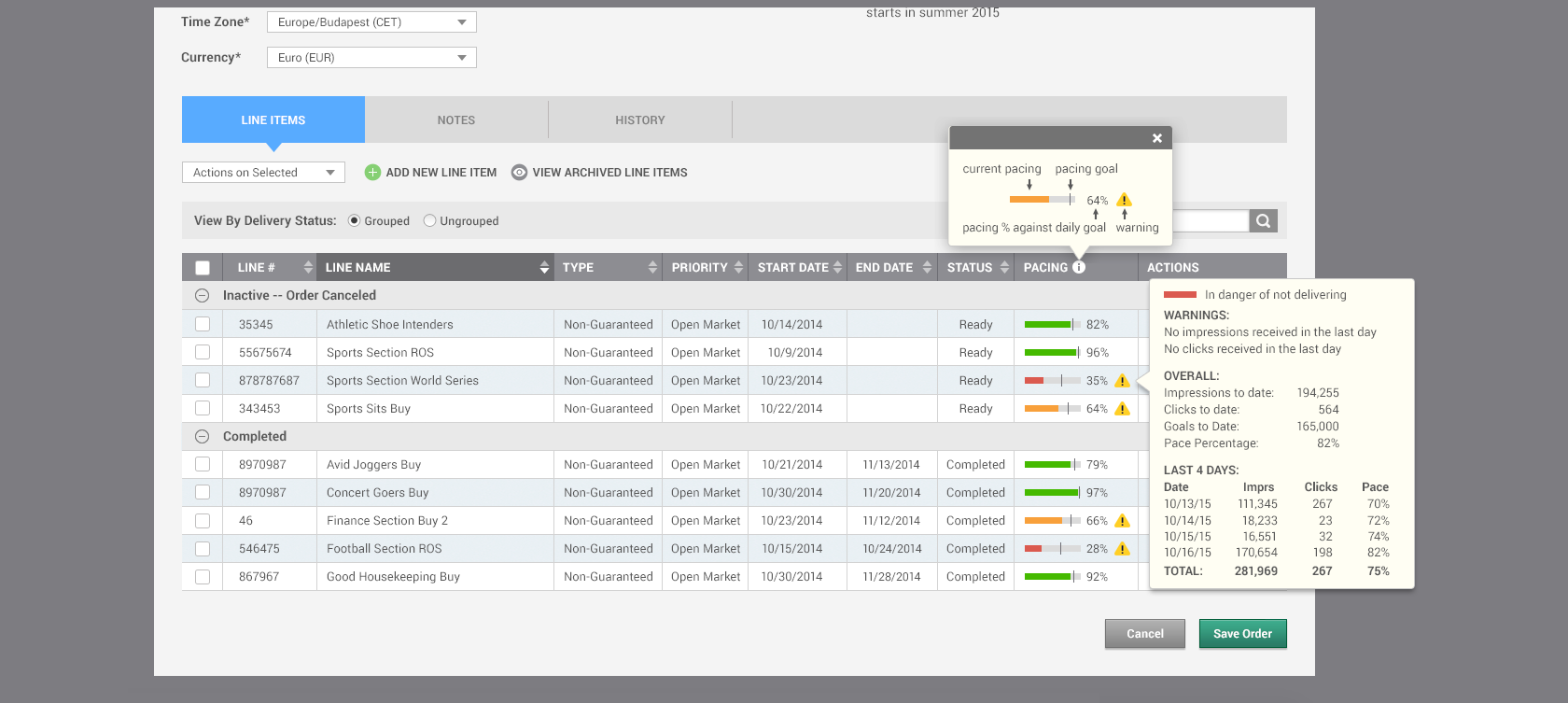

6. UX Wireframes

A staple of UX design methodology, wireframes are two-dimensional “blueprint” illustrations of a design framework and interface elements, and show what goes where. Primarily a layout tool, they help define the information architecture, the spacing of content, functionalities, the interaction design and intended user behaviors.

Wireframes are bread-and-butter for UX designers and one of the most common deliverables on a project. “Show me your wireframes” is probably heard more often than anything else during a UX designer’s interview.

A major phase in the UX design process, wireframing is a cost-effective way to explore ideas and generate innovative concepts that address customer goals. They’re great tools to quickly ideate beyond sketching, and they come in many different flavors—from low-fidelity (no styling, black and white boxes, greeked text) to high-fidelity (fully styled, color, very detailed).

Sometimes referred to as “wires” in workplace shorthand, wireframes can save a ton of time and money down the line because they’re so pliable and quick to produce. They serve as a centerpiece around which to have conversations with stakeholders and team members while figuring out the design direction.

Wireframes are foundational, and as such are instrumental in helping to define a design structurally, and how a user flow works through an App or site under different use case scenarios. There are some interesting twists on wireframes such as “wireframe maps” discussed in a previous piece here on the Toptal Design Blogand “wireflows:” a UX deliverable for workflows and Apps from the NNGroup.

Annotated wireframes are one of the most common UX design artifacts (by Miklos Philips)

7. Interactive Prototypes

Another dominant deliverable during a user-centered design process, interactive prototypes breathe life into a product. Rudimentary prototypes save a ton of time and money—they demonstrate how things will work in an actual use case scenario, and allow for rapid design iteration and user testing. They also help a designer communicate their design effectively at different stages of the UX design process.

Prototyping can happen at any point in the journey of discovery through iteration. From paper prototypes to highly polished designs, an internal review of a product prototype lets everyone on the team see how things will work when an actual user interacts with it.

Static sketches and wireframes don’t bring a product to life in a way that an interactive prototype can. Almost magically, it is seen and felt how the product will behave—how everything connects. Different designs and features can be explored; new ideas may emerge. Trouble spots can be spotted and awkward interactions uncovered.

Interactive prototypes help user testing immensely. Rather than walking people through static pages, potential users can test a product that feels 100% real, provide ideas and give valuable feedback.

These days, prototyping tools for designers come in all shapes and sizes. Here are 21 interactive prototyping tools for UX design.

Interactive prototype for UX design exploration and usability testing (by Miklos Philips)

8. Visual Design

Visual design is the “final coat of paint” on the product. However, it’s not just that: visual design can greatly affect the UX of a product, and therefore must be approached very carefully. Hopefully, a lot of interaction design and usability heuristics were worked out during prior steps of the UX design process so that the designers can focus on the visuals. It’s one last opportunity to take the product to the next level.

Visual design is the last step before handoff to developers and the phase where a styleguide and final specs are crafted. It’s not just about “making things pretty,” but an opportunity to define, or implement a brand color-scheme and affect usability with the layout, contrast, and visual hierarchy.

Visual design as the final UX design process step after sketches, wireframes, interaction design and prototypes (by Miklos Philips)

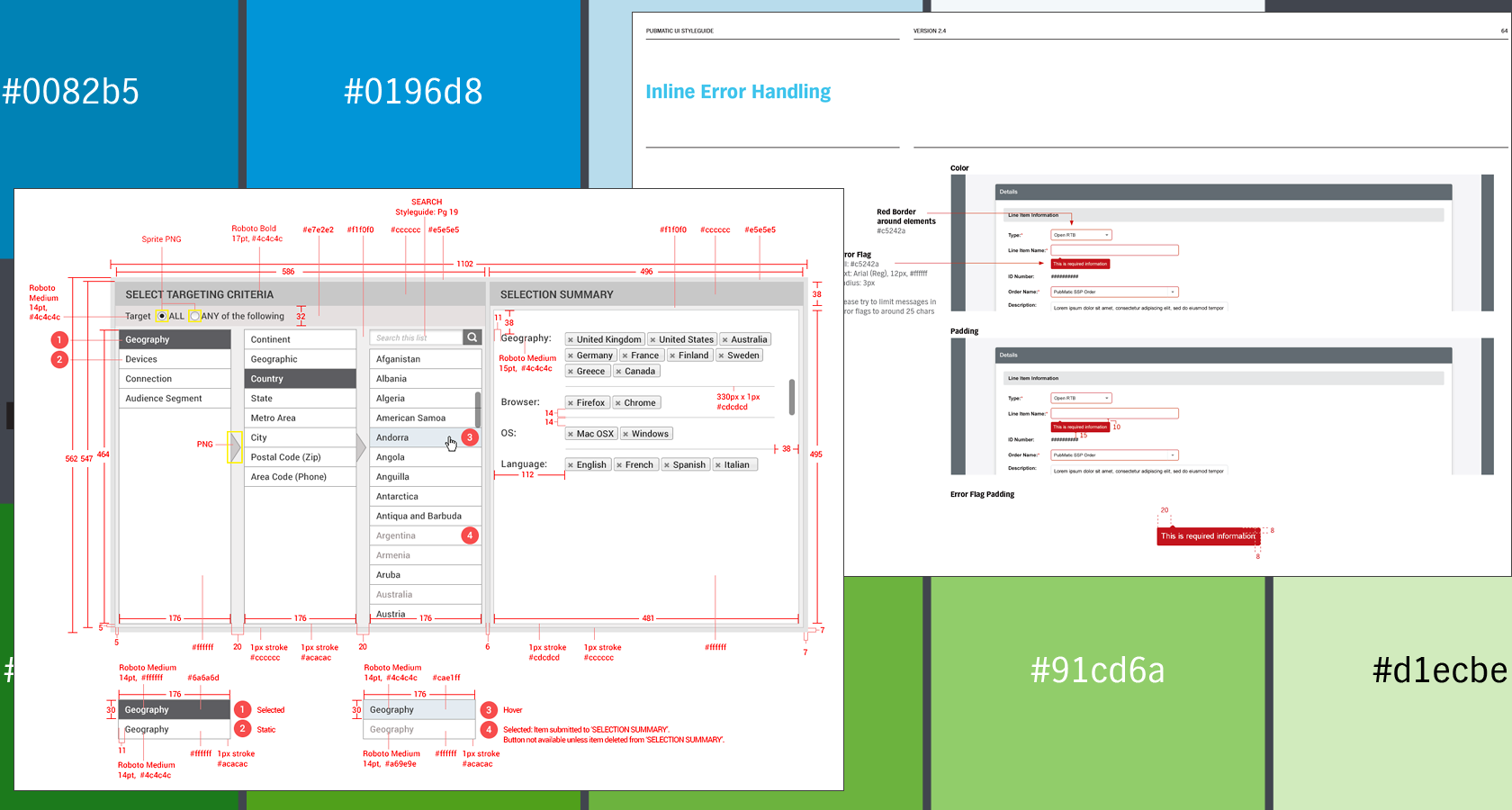

9. Styleguide and Specifications for Developers

The final step in the UX design workflow is to put together specifications and a styleguide for developers. Styleguides are a must if a product’s design is to succeed in the long run.

A styleguide is for making sure designs are implemented consistently across branding, visual styles, colors, fonts and typography. It’s also used for design patterns, language, rules (such as keyboard shortcuts and data display rules), and specifying UI behaviors (such as error handling).

Some styleguides and specifications are put together manually, and others are generated automatically. Putting together a styleguide manually is a tedious process and can often take six months, so any automation tool is a welcome timesaver.

The automated ways vary depending on the tool used. They are a more agile, incremental way to handoff designs vs. styleguides crafted over a long time. They can be thought of more like “bibles of style” on the shelf that everyone on the team can refer to.

If you work in Sketch there are god-sends such as Zeplin. Zeplin is a collaboration tool for UI designers and front end developers. It goes beyond the design workflow and helps teams with the design hand-off.

In addition, a design styleguide can be generated in a few seconds from Sketch with the Craft plug-in, or measurements and CSS grabbed from the design by generating an HTML file with the Marketch plug-in as outlined in this article.

Here are 50 great styleguide examples. Also one from the BBC, and one from IBM, both of which host their guides online which makes it easy for everyone to view it.

Styleguide and specifications for developers the final step in the UX design process

10. Usability Testing and Usage Analytics Reports

A UX designer’s job is never done. Even after a product’s release there are opportunities to gather feedback, collect data on usage, refine, release and start the cycle all over again.

A usability test will tell you whether your target users can use your product. It helps identify the problems people are having with a specific UI, and reveals difficult-to-complete tasks and confusing language.

Usability testing reports are typically delivered during the prototyping phase, but it’s not unusual to test existing products with users to see where there may be room for improvement.

Understanding data gathered during usability testing—collecting, sorting and the generation of reports, is becoming an increasingly common task among UX practitioners—in fact, it’s becoming a critical UX skill. Here’s a usability testing report template.

After the product is released into the wild another set of data gathering—a quantitative method—will tell the design team how the product performs with users on a mass scale.

There are countless tools and ways to capture user behavior and analyze it. From eye-tracking to click-tracking and heatmaps (which show clicks, taps, and scrolling behavior) to UI element tagging which tracks the digital footprint of every user across mobile and web devices.

Analytics reports show which features customers use, how much time they spend on your mobile App or site, trends over time—and they aggregate results across geographies, accounts, users, and custom segments. They provide full visibility into how features are being used and by whom.

Analytics companies usually automatically generate customized reports on demand. These reports are very useful and can provide surprising insights into your product’s usage. That amazing feature you thought would win over all your customers may turn out to be hardly ever used. On the flipside, a small, insignificant function in the UI may prove to be getting a lot of use and you may decide it’s time to focus on expanding that particular functionality.

Usability testing reports

A UX designer’s mission is to empower companies to make products and services based on a deep understanding of human behaviors, goals, and motivations. The 10 UX deliverables above are some of the most common produced by UX Designers as they craft great experiences for users as part of “design thinking” and a user-centered design process.

POST ORIGINALLY WRITTEN BY MIKLOS PHILIPS – UX DESIGNER AND DESIGN BLOG EDITOR @ TOPTAL